One of the first articles I wrote for Spinal (con)Fusion was an article explaining adjacent segment degeneration (ASD). This is a dreaded outcome after spinal fusion in which the motion segment adjacent to a previous fusion becomes symptomatic and ultimately requires extension of the fusion to the newly affected level. It’s been almost 10 years since I wrote that article and we still don’t really know why ASD occurs in some patients but not others after fusion. There are some surgical variables that have been clearly associated with the development of ASD (remember, though, that an association doesn’t necessarily imply direct causation). Here’s what I believe to be true:

1. I do believe that the use of open, posterior approaches to the spine versus minimally-invasive, anterior ones can weaken the supporting structures of the spine and thus lead to ASD.

2. I also think that if proper attention isn’t paid to restoring sagittal imbalance (either under- or over- correcting) ASD is likely to occur.

3. Lastly, if the surgeon isn’t careful in placing pedicle screws and violates the facet joint of the level above, that facet joint violation likely leads to ASD.

Readers of Spinal(con)Fusion know that I rarely, if ever, perform open spinal fusions so that takes care of number 1. Also, I’m not perfect but I almost always avoid fusing someone without restoring or at least preserving sagittal balance. Lastly, I rarely violate facet joints while placing percutaneous pedicle screws. Still, though, some of my patients in which I’ve committed none of the above sins still get ASD.

I erroneously used to think that my rate of ASD was quite low. It turns out I just wasn’t following the patients long enough; sometimes it can take decades for ASD to develop. Now that I’ve been in practice in Wilmington for 10 years, I’m starting to see patients come back with ASD. To be fair, when I look at my rate of ASD it’s 4.4% percent across about 1000 fusion patients (slightly higher when the fusion is at L4/5 and above and slightly lower when L5/S1 is included in the construct as I’ll discuss below.) This is still on the very low end of the range of rates of ASD reported in the literature, probably because I am meticulous in avoiding the three factors above (and to some degree I still haven’t followed my patients long enough.) Despite this care, however, patients are still coming in for extension of their fusions. Talk about frustrating!

A deeper dive into my data reveals something else that I’ve been missing that may be leading to cases of ASD: I think I’m not being aggressive enough in treating pathology at L5/S1 when treating pathology at L4/5. When I look at cases only involving XLIF at L4/5 and above, my rate of ASD is 8.7%. For cases in which L5/S1 is included, however, the rate is much lower at 3.0%. What this tells me is that there were some patients in the XLIF cohort that didn’t get a fusion down to the L5/S1 level when they probably should have. To be fair, many of the XLIF patients who developed ASD after their XLIF had their surgery before we developed LALIF for treating L5/S1 with the patient remaining the lateral position (without this excellent treatment option I was probably putting my head in the sand about some L5/S1 levels that should have been treated.) Not all of them though. As part of my minimally-invasive mindset I try to be as targeted with my therapy as possible rather than aggressively fusing every level that is showing even the slightest signs of wear. In a patient who is clearly only symptomatic from a mobile spondylolisthesis at L4/5, for example, I’m likely only going to treat the L4/5 level, even if there’s already some mild wear and tear at L5/S1 (see case below.) Even with the efficient, minimally-invasive LALIF procedure, treating L4/5 and L5/S1 concurrently is more complex, takes longer and is riskier than just treating L4/5 alone. So is the disease at L5/S1 really worth treating given the extra morbidity of the abdominal approach of LALIF? This is what I’m constantly juggling in my mind when I’m talking to patients about fusion at L4/5. It’s a balancing act for sure and there’s no algorithm that clearly guides us here.

Really, though, I think I’ve just been too hard on myself. I used to take it personally when a patient came back in needing an extension of their fusion–I considered it a failure of treatment that I somehow caused. However, my thinking on the subject has evolved dramatically in recent years. Rather than treating diseased motion segments in isolation (and thus beating myself up when a new problem at an adjacent segment arises), I now understand that I’m really just managing a lifelong, progressive condition. The degeneration of your spine is a chronic disease. Just like other chronic diseases there are things you can do to slow or even halt the progression of the disease. Things like weight control, core stability and weight-bearing exercise are arguably more important in the treatment of your disease than anything I can do for you. In the end, though, it may catch up with you anyway, whether you’ve had a fusion or not. Does a previous fusion accelerate degeneration at adjacent levels? Probably. In my opinion, though, given the chronic, progressive nature of degenerative disc disease, the degeneration of the segment was likely to happen anyway. So is it not worth getting the initial fusion in the first place even if it’s only going to buy you, say, 5 more years of significantly reduced pain before you may require another fusion? This is a tough question that many of my patients struggle with. In the end, I’m here to try to manage the flare ups of this chronic disease. This is a balancing act between sufficiently putting out the fires when they arise and not exacerbating the problem with overly aggressive treatments. On good days this feels like I’m elegantly threading a needle, on other days it just feels like a game of Whac-A-Mole.

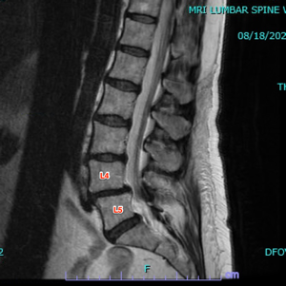

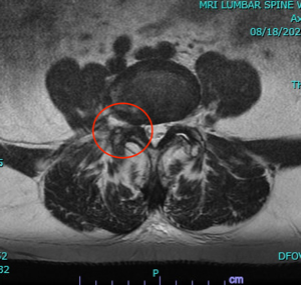

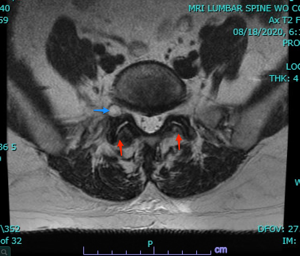

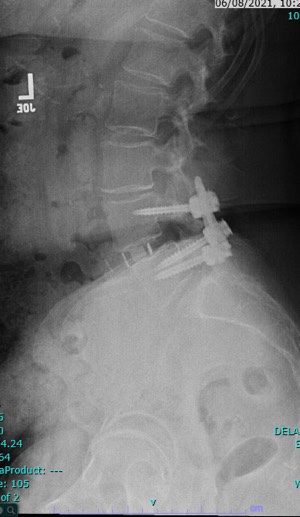

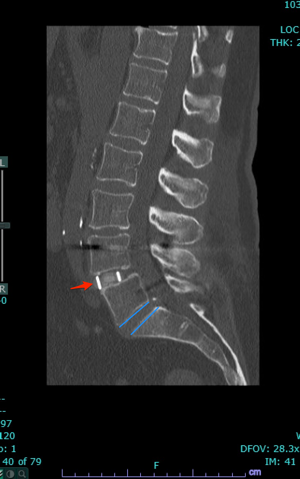

I’ll close with a case presentation of a patient that I just saw last week. The patient is a 63-year old female who is a nurse at one of our local hospitals. She’s an awesome patient: extremely motivated, energetic and knowledgeable about what ails her. She presented in early 2021 with about 1 year of worsening pain in her right leg. I felt that this pain was secondary to the severe foraminal stenosis associated with an unstable spondylolisthesis at L4/5. (See figure 1) In addition to her spondylolisthesis she also had early degeneration at the L5/S1 level, particularly on the right side where she also had a facet cyst indicative of advanced arthritis in the facet joint. (See figure 2) I was a bit nervous about just doing a fusion at L4/5 and leaving L5/S1 alone. We talked it over together and, as I always do, I involved her in the decision-making process. She understood that there potentially could be an issue at L5/S1 down the road but also understood the potential downsides of the abdominal approach needed to properly fix L5/S1 concurrently. In the end we both decided that we’d just fix the level causing her immediate symptoms and keep our fingers crossed that L5/S1 would hold. She felt that she’d be able to bounce back and get back to work more quickly after just a one-level fusion. We did an XLIF and perc screws at L4/5 in March 2021 and she did great. (See figure 3) She went home the next morning with near complete resolution of her leg pain. She progressed very well and was essentially pain free…for about 16 months. Unfortunately, in late summer 2022 she began having back pain as well as a new pain in the posterior aspect of the right leg (a different nerve distribution than previously.) Updated imaging reveals severe degeneration of the facets at L5/S1 with a spondylolisthesis. (See figure 4) Frankly, I was shocked at how quickly this degeneration had progressed (her routine post-op CT scan, when she wasn’t having any pain, actually showed the early slippage at L5/S1, see figure 5.) She’s just agreed to have an extension of her fusion down to L5/S1 and will undergo the procedure in the coming weeks. What does this case show us? Well first it shows that ASD can develop rather quickly in some rare cases. Second, it highlights the notion that perhaps I need to be more aggressive in recommending surgery at L5/S1 in addition to L4/5. Lastly, it shows that sometimes ASD just happens. Even without the fusion I’m certain that, as quickly as it degenerated, the L5/S1 level was already compromised and was likely going to degenerate to the point of needing surgery anyway. What she probably needed was a L4-S1 fusion but she doesn’t regret initial surgical plan at all. She made an informed decision about the right treatment for her at the time and she was able to live pain-free for nearly a year and a half. She’ll do great after her extension and hopefully won’t require any further surgery.

Figure 1: Preoperative sagittal (left) and axial (center) MRI images showing grade I spondylolisthesis at L4/5. Axial images shows severe right facet hypertrophy at resultant foramina stenosis (red circle). Flexion X-rays show worsening of the spondylolisthesis with flexion (blue lines, right image).

Figure 2: Preoperative axial MRI at L5/S1 level showing mild facet arthritis (red arrows) and R-sided foraminal facet cyst (blue arrow).

Figure 3: postoperative lateral Xray showing XLIF spacer and pedicle screws in good position with reduction of spondylolisthesis.

Figure 4: Updated sagittal and axial MRI (left and center images) showing severe degeneration at L5/S1. On the axial image note the severe facet arthritis (red arrows) and new left sided facet-cyst (blue arrow). If it weren’t for the hardware at L4/5 I wouldn’t have believed it was the same patient. Flexion Xray (right) show worsening of the spondylolisthesis at L5/S1 on flexion (blue lines)

.

Figure 5: 6-month postoperative CT scan showing XLIF spacer in good position at L4/5 (red arrow) but also now a slight spondylolisthesis developing at L5/S1 (blue line on the bottom of L5 is sliding forward slightly compared to the blue line at the top of S1).

Thanks for reading,

J. Alex Thomas, M.D.